It was 2016 when Jurandir Jekupe seen the bees have been gone.

Their nests have been as soon as widespread in Yvy Porã, the Guarani Mbya village the place Jekupe grew up and nonetheless lives. However now the uruçu, a species identified for its honey, had all however vanished, and sightings of the jataí, a species sacred to the Guarani Mbya, have been uncommon.

“Bees are very delicate,” says Jekupe, a pacesetter in his Indigenous group. “They’re like a thermometer for the forest. In the event that they disappear, there’s one thing fallacious.”

Yvy Porã is certainly one of six villages that make up the Jaraguá Indigenous Territory. It lies simply 12 miles northwest of downtown São Paulo and is surrounded by the concrete of working-class neighborhoods. However this small forested space is a part of a a lot bigger complete — Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, a site that covers nearly 35,000 sq. miles, working alongside greater than 1,800 miles of the Atlantic Coast, sweeping throughout 17 Brazilian states, and dipping into Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

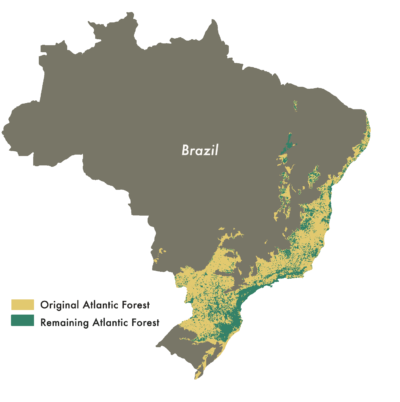

Logging of this forest — nonetheless thought-about the second largest rainforest in Brazil — started within the early 16th century as land was cleared for timber and mines after which, within the 19th century, for espresso plantations, beef, sugar, firewood, and charcoal. Right this moment, builders proceed to clear the Atlantic Forest for housing, because the populations of São Paulo — at present house to 12.4 million folks — and Rio de Janeiro explode.

Indigenous peoples in Brazil are broadly considered land protectors, and a brand new examine of the Atlantic Forest confirms it.

Because the forest has fallen, so have populations of native bees. And with out the pollination they supply, the forest that is still — in locations like Yvy Porã — has struggled to outlive.

So the Guarani Mbya determined to do one thing about it.

A nomadic folks, they usually journey to different villages throughout the forest, visiting household and exchanging data. On a visit in 2016, residents of Yvy Porã discovered that villagers within the state of Espírito Santo, which had additionally misplaced its native bees, had began shopping for bees, elevating them in picket hives, and reintroducing them to their land. The Guarani Mbya determined to deliver the thought again with them to São Paulo.

And it labored.

Based on a examine revealed within the journal Ecological Functions, the restoration and conservation of tropical forests in Brazil is determined by plant species that depend on bees for pollination. Whereas trying particularly on the Atlantic Forest, the researchers concluded that conserving bee populations must be a precedence for forest restoration.

“There’s a distinction now,” says Márcio Mendonça Boggarim, chief of Yvy Porã and its head beekeeper. “The bees are thriving and the vegetation now we have been reintroducing to our land have been doing higher, rising extra.”

Left: Jurandir Jekupe of the Guarani Mbya tends to a beehive within the village of Yvy Porã within the Atlantic Forest. Proper: An uruçu stingless bee in certainly one of 110 beehives in Yvy Porã.

Jill Langlois

Each the bushes and the bees, it turned out, wanted a hand from the individuals who lived amongst them and had a deep connection to their land.

Indigenous peoples throughout Brazil are broadly considered land protectors, and a brand new examine of these residing within the Atlantic Forest confirms it. Not solely do Indigenous peoples push again towards additional makes an attempt at deforestation, the examine discovered, in addition they provoke initiatives to revive biomes just like the Atlantic Forest, together with the reintroduction of native bees and the planting of bushes and different vegetation that have been way back worn out by outsiders.

However like many different Indigenous teams residing within the Atlantic Forest, the Guarani Mbya are working at a drawback. They lack monetary assist from outdoors their group and, most significantly, from the federal authorities, which has but to grant them tenure to the whole thing of their land, which on the Jaraguá Indigenous Territory covers some 1,315 acres. And with out this official recognition, their efforts to boost cash for restoration efforts are much less efficient than they may very well be, leaving the Atlantic Forest weak to much more loss.

Added to the World Heritage Checklist by UNESCO in 1999, the South-East reserves of the Atlantic Forest — and different elements of this biome — are house to well-known species like jaguars, sloths, golden lion tamarins, and toucans, along with lesser-known species like thin-spined porcupines and Bocaina treefrogs. Based on the World Wildlife Fund, one hectare of Atlantic Forest can assist 450 species of bushes. Of its 20,000 vascular plant species, about 8,000 are endemic, which means they happen nowhere else on the earth.

“The Atlantic Forest has additionally been largely ignored on the subject of Indigenous peoples,” says a researcher.

Whereas an estimated 83 % of the Amazon rainforest, which usually makes headlines for its rampant deforestation, remains to be intact, solely about 12 % of the Atlantic Forest stays standing. It’s a proportion that worries scientists.

Most consultants advocate sustaining 30 % of forest cowl to keep up biodiversity, says Rayna Benzeev, a postdoctoral analysis fellow on the College of California, Berkeley, who research the restoration of tropical forests, with an emphasis on the Atlantic Forest. As soon as forest cowl dips beneath that threshold, natural world are vulnerable to disappearing.

Worldwide, Indigenous communities are more and more seen as the very best protectors of forests. Based on the World Assets Institute, lands beneath Indigenous management within the Amazon undergo much less deforestation than these outdoors Indigenous management and so are usually internet carbon sinks, relatively than internet carbon sources. And environmentalists more and more acknowledge that forest communities usually make higher custodians of their forests than do formally protected nationwide parks.

As a part of a current examine revealed within the journal PNAS Nexus, Benzeev and her coauthors checked out 129 Indigenous lands within the Atlantic Forest. There, they discovered both much less deforestation or elevated reforestation the place Indigenous folks have formal rights to their land, in contrast with Indigenous communities that lack official rights to their land.

Supply: Pinto & Voivodic, 2021.

Yale Setting 360

Based on the examine, every year after tenure was formalized, forest cowl elevated 0.77 % in contrast with Indigenous territories that have been untenured. It’s a discovering that highlights the significance of granting formal land title to Indigenous communities within the forest.

“The Atlantic Forest has additionally been largely ignored on the subject of Indigenous peoples,” says Benzeev, who carried out the examine whereas receiving her PhD in environmental research on the College of Colorado, Boulder. “However you will need to bear in mind what number of Indigenous lands and peoples there are within the Atlantic Forest,” which can be house to nearly all of Brazilians, most of whom dwell in giant city facilities.

For the Guarani Mbya residing on the Jaraguá Indigenous Territory, land tenure has lengthy been a fancy and making an attempt problem. On paper, the Indigenous group has tenure over simply 4.2 acres of land, sufficient area for the 70 folks residing in Ytu, certainly one of six Guarani Mbya villages. The remainder of the 700 Guarani Mbya residing on the territory, together with these in Yvy Porã, occupy land for which they don’t but have official tenure. As soon as land is beneath the tenure of Indigenous peoples in Brazil, the federal authorities is required by regulation to guard it. If outsiders try and invade and deforest the land, authorities are required by regulation to take away them, though these legal guidelines haven’t all the time been enforced, particularly throughout the current administration of Jair Bolsonaro, who served as president from 2019 to 2022.

For many years, the Guarani Mbya have sought official tenure of their lands, however their petition has remained stalled.

The Guarani Mbya have, for many years, sought official tenure for the virtually 1,315 acres they already dwell on; the federal government addressed their request most lately in 2015. Their petition went via many of the required steps, however then, like many different petitions for land tenure in Brazil, it stalled. All it wants now’s a signature from President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and official registration.

Throughout his election marketing campaign, Lula, because the president is thought, promised to signal land tenure decrees for all 237 pending requests from Indigenous peoples, saying it was “an ethical dedication, an moral dedication for individuals who are humanists, for individuals who defend Indigenous peoples.” His authorities has since mentioned that tenure for the primary 13 Indigenous territories can be finalized by the top of this month; the Jaraguá Indigenous Territory isn’t amongst these territories.

Because the Guarani Mbya’s authorized battle continues, so does their work to revive their piece of the Atlantic Forest. Some residents of the territory give attention to eradicating invasive species from the forest: Espresso vegetation nonetheless run rampant on their land, displacing native species, and outdated plantations of eucalyptus have been inflicting issues too, sucking up an excessive amount of water and resulting in overly dry soil and erosion. The Guarani Mbya have been changing these vegetation with native species like brazilwood, mate, and palmito juçara.

A river within the Atlantic Forest close to Ubatuba, Brazil.

Octavio Campos Salles / Alamy Inventory Photograph

They’ve needed to buy seedlings and saplings, Jekupe says, chuckling at one small tree lately planted subsequent to a grouping of beehives. It nonetheless has a price ticket hanging from its skinny trunk. “Forty-five reais,” he says as he turns it over in his hand. “Who would have thought we must pay for bushes for our personal land?”

Others work alongside Boggarim, the Yvy Porã chief, studying to take care of the eight species of native bees he’s introduced again to the village. The foot-tall picket containers with corrugated tin roofs stand on poles among the many bushes, every with a species-specific opening in its entrance the place bees, all stingless, zip out and in. He has positioned their 110 hives in groupings round Yvy Porã, a strategic plan to ensure the bees and the forest might help one another equally.

“Defending our territory, reforestation, elevating native bees: It’s all one job,” says Boggarim. “We are able to’t consider them as particular person duties. With out one, we will’t have the others.”

Boggarim’s father and grandfather first taught him concerning the significance of the insect to the forest and their tradition. The jataí’s wax, for example, is became candles utilized in Guarani Mbya naming ceremonies and for making different sacred objects important to their prayer homes. Now Boggarim passes that data to youthful generations, together with what he’s discovered from different beekeepers about easy methods to monitor the bugs and ensure they’re wholesome and thriving.

“If we need to save the forest, we’d like the federal government to formally acknowledge that that is our land.”

Boggarim has helped deliver bees into 5 villages on the Jaraguá Indigenous Territory and has plans for a sixth, and he’s enthusiastic about how they will begin producing and promoting honey. It might not solely present native households with a lot wanted earnings, however would additionally assist them share their tradition and the significance of the forest with folks outdoors their group.

Already, the Guarani Mbya work with colleges to supply instructional excursions on their land. However with out tenure for all of their land, it’s been a battle to get some initiatives off the bottom.

For instance, Jekupe explains, most of their initiatives require assets to be shipped in from out of state — their bees got here from the Guarani Mbya village in Espírito Santo, some 705 miles away, and a few of their vegetation got here from so far as Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil’s most southern state. Funding for these initiatives usually comes from NGOs and authorities our bodies, however within the absence of land tenure, some donors draw back from these initiatives, apprehensive that paperwork and conflicts might deliver them to a halt.

“If we need to save the forest, we’d like the federal government to formally acknowledge that that is our land,” says Jekupe. “We’re those who see the results of deforestation, who really feel the results of local weather change, each single day. And in the event that they step out of the way in which, we’re those who can do one thing about it.”