For greater than 4 a long time, Kokoró Mekranotire has watched with dismay as outsiders have laid waste to ever-larger swaths of his Kayapó homeland. Loggers, gold miners, farmers, and land grabbers have streamed illegally into and across the Indigenous territory, a 40,000-square-mile expanse of forest the scale of South Korea. The patch of forest the place Mekranotire used to gather Brazil nuts — a dense cover of deep golden-brown bushes standing nearly 100 toes tall — was stripped. Stands of cumaru bushes, a Brazilian teak, have been felled to make decks, cabinetry, and flooring. Loggers have repeatedly entered Kayapó land, eliminated what was of their means, and brought the remaining to make a revenue.

“These bushes by no means ought to have been touched,” says Mekranotire, now 49 and dealing for the Kabu Institute, a nonprofit that helps shield Kayapó land and develop sustainable companies amongst its folks, together with Brazil nut cultivation. “We needed to struggle to carry onto our land and let extra bushes develop.”

Outsiders began arriving in droves within the Seventies with the opening of the federal BR-163 freeway, which stretches 1,320 miles from Cuiabá in south-central Brazil to Santarém within the coronary heart of the Amazon. BR-163 parallels Kayapó land and was absolutely paved by 2020, spurring a increase in soybean farming, with the freeway offering easy accessibility for hundreds of thousands of tons of the commodity crop to achieve Brazilian ports.

“We’re preventing a battle in opposition to politicians who need to destroy us and our land,” says a Kayapó activist.

The paving additionally supplied a lot simpler exterior entry to 2 vital Kayapó reserves, Menkragnoti and Baú, measuring greater than 18,000 sq. miles and 6,000 sq. miles, respectively. Unlawful loggers and miners who used to reach in a trickle, Mekranotire says, began gushing in. “The kuben [white men] already had quite a lot of expertise; they knew precisely what they have been doing,” he says. “However not all of our leaders did. They informed us the freeway wouldn’t have an effect on us. It was a lie.”

Now, as Brazil’s nationalist President Jair Bolsonaro continues his push to legalize a broad vary of financial and extractive actions on Indigenous land, plans are underway for a railway to assist transport soybeans from the area’s burgeoning variety of farms. And despite the fact that the Kayapó are one of many strongest and best-known Indigenous teams within the Brazilian Amazon — they’ve led the struggle for Indigenous rights for 40 years — Bolsonaro’s anti-Indigenous insurance policies are posing a big menace.

“We’re preventing a battle,” says Doto Takakire, who additionally works on the Kabu Institute. “A battle in opposition to politicians who need to destroy us and our land.”

Situated on a plateau in central Brazil, far south of the Amazon River and within the states of Mato Grosso and Pará, Kayapó land is the most important tract of Indigenous territory in Brazil and the most important swath of comparatively pristine forest within the Amazon’s southeast, a area often known as the ”arc of deforestation.” Regardless of persevering with incursions — the Kayapó misplaced 3 million acres of land on their jap border to logging, mining, and different improvement within the Nineteen Eighties and Nineteen Nineties — the group’s territory retains exceptional biodiversity, with jaguars, large otters, harpy eagles, considerable fish populations, and huge forest areas.

Kokoró Mekranotire of the Menkragnoti Velho village on the Menkragnoti reserve.

Numbering solely 9,400 folks, the Kayapó reside in villages on the Xingu River and its tributaries. The boys fish and hunt animals resembling tapir, capuchin monkeys, peccary, and deer. Girls increase youngsters, have a tendency in depth gardens, and make journeys into the forest to gather Brazil nuts, cumaru, açaí berries, and different fruits.

Within the Nineteen Eighties and Nineteen Nineties, the Kayapó made worldwide headlines as they moved to acquire authorized rights to their conventional lands. Led by Chief Raoni Metuktire, who would ultimately be nominated for the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize, they have been joined by musician Sting of their struggle to guard the Amazon rainforest, spawning nonprofits just like the Rainforest Fund. Different teams, such because the Worldwide Conservation Fund of Canada and Conservation Worldwide, have helped the Kayapó defend their territories, offering boats, radios, and aerial surveillance information so the Kayapó can patrol their 1,250 miles of border.

“If there have been no extra Kayapó territory, then there would undoubtedly be no extra forest in any respect,” says Renata Pinheiro, senior supervisor for Indigenous folks and social insurance policies at Conservation Worldwide Brasil. “They’re on the agricultural frontier.”

The Kayapó’s struggle has been half of a bigger motion to demand Indigenous land rights in Brazil following centuries of oppression. The implementation of Brazil’s Structure in 1988, together with article 231, which outlines these rights in addition to the federal authorities’s accountability to demarcate and shield the land, gave them recourse. It didn’t, nonetheless, imply that these theoretical protections would at all times work in follow.

Left: Kayapó girls carry bundles of leaves to a village ceremony. Proper: Kayapó males in a standard ceremony.

Within the a long time to come back, all Indigenous land — Brazil has 305 Indigenous teams — would proceed to come back underneath menace, whether or not or not the teams had already accomplished the sluggish strategy of demarcation and official authorities recognition. Unlawful mining, logging, fishing, and land theft, in addition to the development of highways, railways, and hydroelectric dams, have continued to impinge upon Indigenous territories.

The Yanomami, who reside within the Amazon rainforest bordering Venezuela, are nonetheless in a longstanding struggle to take away greater than 20,000 unlawful miners from their land, which is wealthy in gold. In Mato Grosso do Sul — a state that encompasses the tropical savanna often known as the Cerrado and the world’s largest tropical wetland, known as the Pantanal — the Guarani Kaiowá are attempting to take again land misplaced to ever-advancing farming, going through violent assaults and the burning of their prayer homes. And the Kambiwá, Pataxó, and Pataxó Hã-Hã-Hãe within the state of Minas Gerais, who misplaced their land within the 2019 Brumadinho dam catastrophe, proceed to confront land grabbers attempting to take over their new territory.

The development of the BR-163 freeway was a part of the Nationwide Integration Plan applied by Brazil’s navy dictatorship — a challenge designed to carry Indigenous teams underneath authorities management, occupy the Amazon, and take over the land. Something and anybody in the way in which could be eliminated.

Kayapó land ravaged by unlawful gold mining.

By the point the freeway opened in 1976, many Kayapó had succumbed to outbreaks of illness delivered to the area by outsiders, and simply 20 p.c of the Kayapó dwelling on what would turn into the Baú reserve survived. They now not had entry to the Jamanxim River and misplaced 1,158 sq. miles of land to wildcat miners, loggers, and squatters, which they agreed to surrender in change for what could be an empty promise to place an finish to invasions of their territory.

With their land positioned underneath federal safety — the Baú reserve in 2008 and the Menkragnoti reserve in 1993 — the Kayapó thought the threats would subside. However they haven’t. Deforestation has continued to threaten each reserves, as an increasing number of bushes are felled nearer to their borders. In keeping with the Kabu Institute, the deforestation on non-Indigenous land surrounding the Menkragnoti and Baú reserves nearly tripled in 18 years, leaping from 4,450 sq. miles in 2000 to greater than 12,580 sq. miles in 2018.

And deforestation on Indigenous land itself — unlawful in Brazil underneath federal regulation — hasn’t stopped. A current research from the analysis institute, Imazon, confirmed that just about 67,000 acres of forest within the state of Pará have been misplaced to unauthorized logging between August 2019 and July 2020. Of that complete, 390 acres have been on the Baú reserve. In keeping with Dalton Cardoso, an Imazon researcher, the south of Pará, the place Kayapó land is situated, comprises considerable old-growth wooden, prized by unlawful loggers. The area’s ever-expanding community of highways, he says, has additionally “given loggers entry to areas that have been beforehand unreachable.”

Kayapó leaders know that the proposed railroad will carry extra soybean farmers near their land.

It has emboldened them, too. Doto Takakire is from the Baú reserve. Due to his work with the Kabu Institute, he typically travels forwards and backwards between his residence within the forest and Novo Progresso, a close-by city that sits on the BR-163. Notorious for being on the middle of August 2019’s Hearth Day — when a bunch of farmers and ranchers acquired collectively to set a collection of coordinated fires within the forest in assist of Bolsonaro and his promise to open the Amazon to extra improvement — the city is a staging level for males working in extractive industries.

Additionally it is the place a few of them put strain on the Kayapó.

Final yr, Takakire says he was approached a number of occasions by loggers on the town. Due to his means to talk to Indigenous folks dwelling in Baú and Menkragnoti, the loggers thought he might persuade the Kayapó to present them permission to work on their land. Understanding it was wealthy in prized ipê wooden, or Brazilian walnut, they supplied Takakire $10,000 Brazilian reais ($2,000) for his hassle. When he mentioned no, they upped it to $20,000 Brazilian reais ($4,000). Once more, he refused.

“I defend my folks’s pursuits,” Takakire says. “If we cease, who will struggle for us? No person.”

In August 2020, the Kayapó arrange a blockade throughout the part of the BR-163 that runs via Novo Progresso. Sporting headdresses and painted faces, they demanded enhancements in well being care, the elimination of unlawful miners from their territories, and, most of all, to be consulted about plans to construct a railway subsequent to their land.

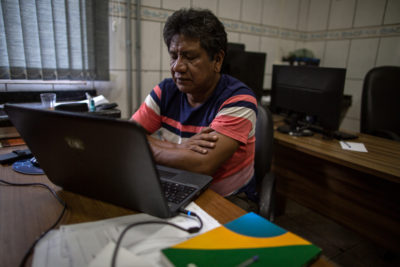

Doto Takakire at his desk on the Kabu Institute in Novo Progresso.

Often known as the Ferrogrão, the railway would run 580 miles between Sinop, in Mato Grosso state, and Itaituba, in Pará, an vital port metropolis for the circulate of agricultural commodities within the Amazon. The railroad’s essential goal: to move soy.

Soy manufacturing in Brazil is hovering, reaching an estimated 134 million tons final yr and making the nation the world’s third-largest soy producer. A research printed final yr famous that soy was answerable for 10 p.c of deforestation throughout South America within the final 20 years, and that “probably the most fast growth occurred within the Brazilian Amazon, the place soybean space elevated greater than tenfold.”

The Kayapó dwelling on the Baú and Menkragnoti reserves don’t must see these numbers to know that soy is taking up the area. The fixed circulate of vehicles carrying soybeans on freeway BR-163 makes it apparent, as do the farms that line the highway. Bepdjo Mekragnotire, chief of the Baú village, situated on the Kayapó’s Baú reserve, is aware of that the proposed railroad will carry extra soy farmers near Kayapó land.

On the Pixaxá and different rivers which might be key arteries via Kayapó territory, warriors have just lately been confronting gold miners illegally coming into Indigenous land on makeshift rafts. The widespread, ad-hoc mining, which makes use of mercury to separate gold from different minerals, has already contaminated quite a few rivers, just like the Curuá, the place the Kayapó as soon as fished, collected consuming water, and bathed. In keeping with a 2018 federal investigation into unlawful mining, fish samples collected within the Curuá and Baú rivers confirmed ranges of mercury effectively above what’s really helpful by the World Well being Group and the Brazilian well being regulatory company, ANVISA.

Left: An unlawful mining raft that entered the Pixaxá River earlier than being ejected by Kayapó warriors. Proper: Fish caught within the Baú river. A federal investigation discovered that fish from the Baú contained excessive ranges of mercury, which is utilized in mining.

No epidemiological research of mercury have been completed among the many Kayapó folks, however their considerations elevated when a research by the scientific establishment Fiocruz and WWF Brazil confirmed that one hundred pc of the members of the neighboring Munduruku Indigenous group have been contaminated with mercury, 60 p.c at ranges above what is taken into account protected. Contamination amongst riverside villagers jumped to 90 p.c.

“We’ve had some infants born with developmental issues,” says Bepdjo Mekragnotire. “We surprise if it’s the mercury, however we simply don’t know but.”

Mining is prohibited on Kayapó territory, however authorized on adjoining land, with the requirement that the Kayapó are consulted concerning attainable environmental and well being results. However, mining is rampant the place the Kayapó reside, often with the involvement of some Kayapó. Wealthy in gold, the complete area has attracted all the pieces from the smallest wildcat operations to a number of the greatest mining giants, together with Serabi Gold, an organization headquartered within the UK that owns and operates two gold mining complexes within the area, together with one subsequent to Kayapó land.

Bekwyitexo Kayapó, chief of Pukany village, holds a basket of beaded bracelets that she and different Kayapó girls make and promote.

Ever since Jair Bolsonaro campaigned for president in 2018, vowing to open up Indigenous land to mining and finish federal recognition of Indigenous territories, the Kayapó have been feeling the strain. Since then, the president has repeated his guarantees a number of occasions, saying two months after his election, “I can’t demarcate yet another sq. centimeter of Indigenous land.”

In 2020, he pushed a invoice to control the exploitation of assets on Indigenous reserves — laws extensively seen as additional opening Indigenous territories to improvement. Brazil’s decrease home of Congress voted this month to flag the invoice as pressing, and it’s anticipated to go to a vote in April. In February, Bolsonaro, who’s up for reelection this yr, signed a decree meant to encourage small-scale and artisanal mining. The federal government has denied this contains unlawful mining, however environmentalists are involved it might spur extra illegal mining within the Amazon.

“Once I was younger, I feared that the white males who got here to our village have been there to kill us and to take what was beneficial from our land,” says Bekwyitexo Kayapó, chief of the Pukany village on the Menkragnoti reserve. “Now, I do know that they’ve come to kill us differently. Now, I worry they’ll do it by taking our land.”