In 2009, as international monetary markets shuddered, David Dorr grew to become eager about the potential for placing a worth on nature. Dorr is a Cayman Islands-based international macro dealer, attuned to what he calls the “butterfly impact” of geopolitics and different worldwide forces on monetary markets. The financial disaster, Dorr had realized, paled beside the looming environmental one. “Nature, holy shit, is in extreme disaster,” Dorr recollects pondering. The existential menace to humanity posed by environmental degradation was “one thing that’s gonna contact each asset class.”

Dorr knew about carbon credit score schemes, through which individuals, governments, or corporations pay for the storage or elimination of carbon from the environment to offset their greenhouse fuel emissions. However he wished one thing broader, a technique to choose the worth of nature not in an extractive sense, nor by the so-called ecosystem providers that nature might present, however by its personal inherent worth.

It has taken longer than Dorr anticipated, however his imaginative and prescient, if not but a actuality, is now not less than broadly shared. Scientists, conservationists, and policymakers world wide are working to develop what they name biodiversity credit. Whereas various intimately, these credit are alike of their function: attaching financial worth to the preservation or restoration of ecosystems.

Just a few corporations at present have biodiversity credit on the market, however many extra are working to develop them.

In broad define, it really works like this. Corporations creating biodiversity credit determine a threatened habitat and type a partnership with the house owners of that land. The corporate or a 3rd get together then conducts a organic survey to ascertain the habitat’s baseline situation, utilizing elements like species richness, ecological integrity, and water high quality. The corporate then devises a plan for enhancing habitat and defending it over a given stretch of time, normally a decade or longer.

At given intervals, maybe yearly or two, the corporate, or the third get together, screens its progress. If the habitat has met the agreed-upon targets of enchancment, it generates a biodiversity credit score, which another person can purchase. Revenues from the credit score are break up between the landowner and the biodiversity credit score developer.

“We solely receives a commission after we ship the efficiency outcomes,” says Mariana Sarmiento, CEO of Terrasos, a Colombian firm that final yr grew to become one of many first to supply biodiversity credit on the market, with 62,000 12-square-yard plots of conserved or restored ecosystems that shall be managed for 30 years. The value is at present round 30 euros per unit, and barely greater than 100 have been bought thus far.

Many individuals hope, like Dorr, that these biodiversity credit will ultimately be standardized, as carbon credit are, with constant contents and worth, and may then be traded internationally within the method of commodities. Packaged like this, they argue, biodiversity credit might present a technique to fund conservation on an unprecedented scale. The necessity is acute: In line with a latest World Financial Discussion board paper, estimates of the price to halt the present international lack of biodiversity are as excessive as $1 trillion yearly. Lower than $150 billion is at present spent on such efforts every year.

A forest in South Australia for which the corporate GreenCollar is creating biodiversity credit.

Accounting for Nature

Though just a few corporations at present have biodiversity credit on the market, comprising most likely lower than a couple of hundred acres, many extra are working to develop them. Already, massive gamers within the carbon credit score business are getting concerned.

There are good causes to be skeptical that the nascent biodiversity credit score business will ship all its proponents say it should. One problem lies in exhibiting that the cash spent on these credit really has its desired impact. This drawback has plagued the carbon credit score market since its inception within the early 2000s. A latest instance got here to gentle this previous January when a joint investigation discovered that almost all of rainforest carbon credit licensed by Verra, the world’s largest certifier of voluntary carbon credit, had been, in truth, nugatory.

However builders of biodiversity credit face one other hurdle, distinctive to their endeavor, which is that not like carbon, which may be quantified utilizing weight-based metrics, biodiversity is diffuse. Even E. O. Wilson, who helped popularize the time period “biodiversity,” struggled to concisely outline it, writing that it encompasses “the totality of hereditary variation in life types, throughout all ranges of organic group” from genes to particular person species to complete ecosystems. Setting a worth for the safety or preservation of such variety is tough. Making use of a constant worth to a biodiversity credit score generated within the Amazon rainforest and one from the Sahara Desert is even tougher.

One firm is creating credit that can every defend one hectare of habitat and its wildlife for not less than 10 years.

Alain Karsenty, an environmental economist on the French Agricultural Analysis Centre for Worldwide Growth, is in favor of biodiversity credit — or “certificates,” his most well-liked time period. However he says he’s “unsure biodiversity certificates will appeal to a big sum of money and consumers.”

The phrase “biodiversity credit score” has appeared within the scientific and conservation coverage literature for not less than 20 years, normally in reference to what are additionally referred to as “biodiversity offsets,” legally mandated in some nations. “You mainly harm habitats of an endangered species in a single space, and then you definitely attempt to rebuild the habitat in one other,” says Paul Steele, an economist on the Worldwide Institute for Surroundings and Growth (IIED). “However that’s fairly difficult to do and nearly by no means works.”

In 2020, Steele printed a paper along with his IIED colleague Ina Porras proposing a brand new use of the phrase. These biodiversity credit, or “biocredits,” would function on a voluntary foundation, underpinned by provide and demand: On the one hand had been those that wished to contribute funding to conservation; alternatively had been conservationists and landowners who wanted funding to try this work. The scheme would be capable of fund safety and restoration of locations wealthy in carbon, like peat swamps, and people poor in carbon, like deserts.

At first, the paper appeared to flop, Steele says. However over the following two years, the concept took off.

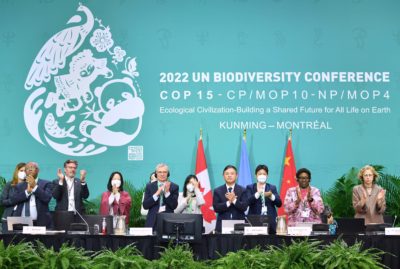

Delegates applaud the the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal International Biodiversity Framework on the UN biodiversity convention in Montreal final December.

Lian Yi / Xinhua through Alamy

Simon Morgan, a South African ecologist, says he and his colleagues got here to the concept of biodiversity credit after watching the Covid-19 pandemic devastate tourism in Africa. “A lot of our conservation efforts are underpinned by tourism,” he says. He thought, “‘Effectively, what else can we do?’” Together with his colleagues, he based ValueNature, which is now creating international biocredits that can every defend or restore one hectare of habitat and its wildlife for not less than 10 years.

Morgan shortly realized that individuals in different components of the world had been doing related work. The idea gained extra momentum late final yr after the events to the Conference on Organic Range adopted the so-called Kunming-Montreal International Biodiversity Framework, which set international conservation targets by 2030. Amongst different issues, the events agreed to supply funding for “modern schemes akin to cost for ecosystem providers, inexperienced bonds, biodiversity offsets and credit, and benefit-sharing mechanisms, with environmental and social safeguards.”

ValueNature is the performing secretariat of the Biodiversity Credit score Alliance, which it based final yr and which is funded by the United Nations Surroundings Programme, the UN Growth Programme, and the Swedish Growth Company. The Alliance’s 80-odd members embrace carbon credit score corporations, tree-planting corporations, universities, laboratories, conservancies, and consultancies, together with plenty of corporations and organizations that intention to develop biodiversity credit.

Members of the alliance agree that they should be diligent in proving that biocredit consumers are getting what they pay for.

The alliance is now working to develop a set of requirements and definitions. One precept that seems to have extensive assist amongst members is that of additionality, which requires biocredits to be based mostly on both measurable enchancment of a degraded ecosystem or safety of an ecosystem beneath imminent and provable menace. Additionality prevents the sale of credit for wholesome land that’s already protected.

Members of the alliance additionally agree, in precept not less than, that they should be diligent in proving that biocredit consumers are getting what they’re paying for. Morgan thinks distributed ledger know-how, or blockchains, might assist with transparency, providing a method for biocredit builders and biodiversity custodians to supply knowledge on to funders on their ecological restoration efforts. ValueNature plans to add the knowledge it collects from digicam traps, bioacoustics screens, and distant sensing applied sciences instantly onto its digital ledger, Morgan says, creating “an immutable knowledge stream.”

Naturally, disagreements exist over what the biocredit business must appear to be. In a 2022 paper, Steele and his IIED colleague Anna Ducros argued that individuals creating biocredits ought to concentrate on assuaging poverty, with the most important share of any revenues going to Indigenous individuals and native communities. Ideally, these populations could be those creating and promoting the biocredits, Steele says, “so it’s extra than simply getting a type of handout from the proceeds that another intermediary or middlewoman — usually a person — is creating.”

A forest restoration undertaking on New Zealand’s Golden Bay developed by Ekos, a startup creating its personal proprietary biodiversity credit score.

Ekos

However Dorr, the worldwide macro dealer, believes there is a crucial position for the middleperson to mediate between the biocredit developer and the biocredit purchaser. In that position, a dealer can make investments cash in tasks in a speculative method, he says, permitting builders to get their undertaking to the purpose of sale. The dealer, he claims, additionally gives an essential layer of vetting for potential consumers, in the meantime, guaranteeing that the credit are accredited and in any other case passable. Pure and unfettered capitalism, together with its middlepeople, he says, is one of the best ways to affix the various potential consumers of biocredits with the various ecosystems in want of conservation and restoration.

However an inescapable hurdle stays: Regardless of lengthy efforts, there may be nonetheless no customary metric for buying and selling. “It’s been a holy grail to a point,” says Nerida Bradley, chief working officer at GreenCollar, an Australian firm now working to develop a proprietary biocredit based mostly on requirements set by a third-party accreditation firm.

Ekos, a New Zealand carbon credit score developer and accreditor that can be a part of the Biodiversity Credit score Alliance, is working by itself proprietary biodiversity credit score. Jemma Penelope, an Ekos senior advisor, thinks it’s unlikely {that a} constant and broadly translatable unit will emerge. “For the time being, we don’t see a single unit of biodiversity ever actually with the ability to give us what we’d like,” she says. “As a result of finally for us, it’s funding communities to take care of their ecosystems. We’re not right here to fulfill the wants of the monetary system.”

It stays unclear whether or not biodiversity credit will ever take off and attain a world viewers.

Others insist a standardized unit is each potential and fascinating. Terrasos, the Colombian biocredit developer, gives an instance of how a common biocredit may work. To evaluate the potential worth in biocredits of a given space of land, the corporate compiles knowledge on the rarity of the ecosystems that land incorporates, its state of degradation and restoration potential, the way it contributes to ecological connectivity, whether or not it incorporates species on the IUCN’s Pink Record, and different elements. It enters these knowledge into an algorithm that calculates the variety of credit that the undertaking can problem. Habitats which can be extra threatened present extra potential biocredits, and habitats which can be much less threatened present fewer.

“Is it good? No,” Mariana Sarmiento says of her firm’s algorithm. “Is it good? I feel so.” Supplied sufficient knowledge, she says, “you’ll be able to apply it wherever.”

It stays unclear whether or not biocredits will ever take off and attain a world viewers. Nonetheless, Dorr can image the ultimate steps: After the biocredits are created and authorized by an unbiased physique, a dealer will assign them a financial worth. Dorr is at present engaged on this course of, considering the everyday price of carbon credit and of ecological preservation and restoration.

Ultimately the suitable worth shall be discovered, he says, and biocredits will flood onto the market adopted by the cash of donors, which is able to circulate to the place it should do probably the most good — a amount of excellent, he says, that can exceed what conservationists can at present think about. “So everyone is comfortable,” Dorr says. “They simply don’t notice it but.”